After my parents died 16 months apart, I inherited a windfall that included my mortgage-free childhood home (valued at $328K) and nearly six figures from their savings. That, combined with a salary in the low six figures and the fact that I’m child-free, meant that I’d be living pretty comfortably, right? Not exactly.

Even though I outearn my much older ex and many of my peers, I feel perpetually poor: In my mind (and some of my actions), I’m still that working-class girl I was growing up, scraping to get by. My father struggled with poverty early in life and was proud of saving enough money to become a homeowner. (During the hospital stay before his death, he asked to return home to die there.)

So my parents’ money sits mostly untouched in my bank account, and I push paying off my $10K credit card debt and waffle on the idea of putting a down payment on a new house because I’m afraid of dipping into my inheritance. For now I’m in my childhood home, paying only utility costs and quarterly taxes and living with memories.

My parents, though they were both Cuban exiles who fled the Communist country in the 1960s, had contrasting and extreme views on money. My mother, Magaly, lived by the philosophy “You only live once,” but just in case, she had knickknacks and clothing to last her two lifetimes. But she also had lighter views on discarding her treasures. A year before she died, my mom handed me two large bags of clothes to donate. “I know it’ll be hard for you to get rid of this when I die, so I’m giving them to you now to help you out,” she said half-jokingly. Mom was right that tossing or donating her belongings after she died would be difficult. Even with her foresight, it took me almost two years to decide what to keep after her death.

At the opposite end of the spectrum was my father, Armando. He’d hide money under mattresses and cushions and wear the same clothes for decades. Dad also refrained from going out for dinners unless it was for special events—and only after we’d pestered him several times. (He would pick the cheapest item on the menu and be shocked when we'd tip between 18 and 20 percent on the bill.) He would resist buying new appliances, even when the old appliances were so worn out that some—like the 25-year-old oven—stopped working altogether.

More From Oprah Daily

Dad and I once got into a heated argument over a rusted 1970s-era lime green chair and the remnants of my baby crib from the early 1980s, which remained enshrined in the basement.

“You don’t understand the value of anything,” Dad told me in Spanish. “Do you know how hard your mother and I worked to get this crib? To get everything you have?” He equated material things with love.

“Dad, this chair is at least a decade older than me, and it’s hideous. As for the crib, even if I were to have a baby, I wouldn’t put them in this death trap,” I retorted. I finally made a deal with neighbors to place these old pieces of furniture on their curbs the next trash day, unbeknownst to my father.

Immediately after my father died, I put the hundreds of dollars of mattress money into the bank. I used some of the money my parents left me on home repairs. A significant portion of my inheritance, $40K, went to a new tub, new windows and floors, and asbestos removal from the basement. I justified these expenses as a good return on investment should I ever sell or rent out my childhood home. But beyond that, I felt remorseful the few times I dipped into that savings account, since I still view my inheritance as my parents’ money.

There’s no separating their money from intense emotions: guilt from knowing that more than 75 percent that sits in my bank came from them, fear from feeling as though I’ll mismanage what they worked so hard to build (or worse, squander it all and be left with nothing).

Tired of feeling this helpless, I recently hired a financial adviser recommended by a trusted friend. We’ve had two meetings via Zoom so far, but I feel more confident. During our second virtual meeting, the adviser and I went through my assets and debts to determine my net worth. This was the first time I’d discussed finances with anyone other than my parents or ex-boyfriend. When the financial planner and I reviewed my savings account, I burst into tears. “I wouldn’t have most of this money if my parents were still alive. I want to be a good steward of what they left me,” I told him, feeling more like I was confessing to a priest or engaging with my therapist than talking to a financial expert. He mentioned he’d push me past my comfort zones, but ultimately, how I’d eventually decide to spend my money (or not) would be up to me.

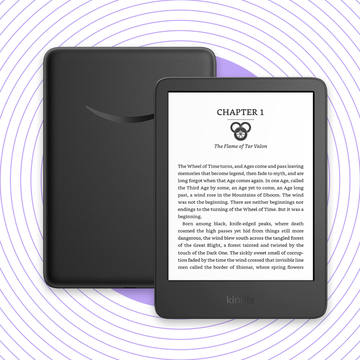

The first thing he suggested was to use my savings to pay down my credit card debt, reminding me that I’m paying more interest by leaving a balance on my cards each month. I may see my savings dwindle temporarily, but I’ll have more money long-term. The adviser will also take a forensic look at what I already spend—er, waste?—my paychecks on. I suspect he’ll advise me to cut back on the number of times I go out to eat, and I don’t have to spend so much on my wardrobe since I already have closets (yes, plural) that rival my mother’s.

The biggest investment I’m weighing, one I’m still ambivalent about, is whether to spend a substantial part of my inheritance on IVF. All the things my parents left me, everything from spending habits to money in the bank, were given with the complicated and consuming love of parenthood. While he couldn’t convince me to keep that baby carriage, I understand that my father’s mania for saving was his way of offering protection and love. Spending my parents’ money, even on preparations for a family of my own is terrifying because now that my parents are gone what they have left behind seems more precious than ever. Perhaps part of me is as reluctant to lose our shared sense of struggle as I am the money they saved. Even if I know deep down that our bond is deeper than debt, I continue to struggle with how to honor the two people who gave me everything.

Carmen Cusido is a writer based in Northern New Jersey. She is working on a memoir about grief and loss titled Never Talk About Castro and Other Rules My Parents Taught Me.