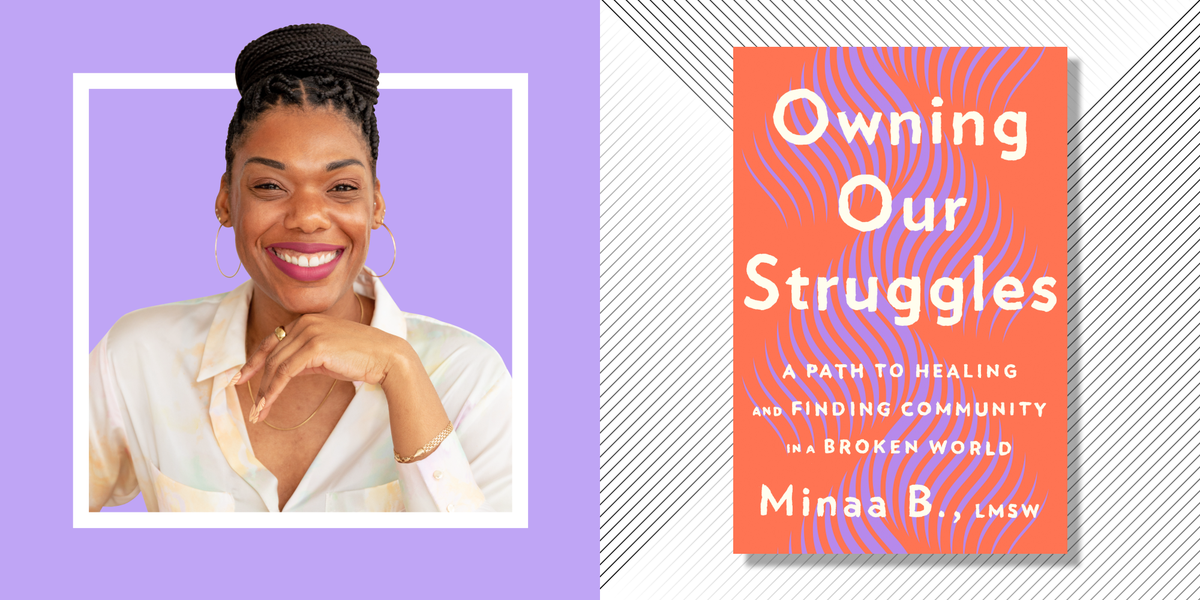

No matter how far you are into adulthood, the idea of ending a relationship with an emotionally abusive parent can make you feel backed into a corner like a little kid. When raging toxicity pummels you from one side and waves of guilt hit you from the other, cutting ties can feel unimaginable. “People are wired to seek affection and nurturing from their parents, and that’s why, despite knowing that our parents might be toxic or unhealthy, we’re always searching for that love,” explains New York City–based licensed social worker Minaa B. “There’s a biological pull.”

In her just-released book Owning Our Struggles, the social worker, author, and writer—who goes by the pseudonym Minaa B.—describes herself as “Black-Hispanic, a woman, and the child of immigrants.” The last of 13 children in a blended family, she was the first person in her family to get a college degree, and the first to continue on to graduate school and earn a master’s degree.

When she isn’t sharing life-affirming guidance with hundreds of thousands of followers via her social media platforms, she is working with companies through her consulting business. She’s also on the advisory committee for the mental fitness company Wondermind, cofounded by Selena Gomez. And this September, she’ll host the latest season of The Verywell Mind Podcast for the mental health platform Verywell Mind. Here, she walks us through one of the hardest decisions a human can make.

More From Oprah Daily

What are some clear signs that you have a toxic or emotionally abusive parent?

If you’re a child, it’s having a parent who physically assaults you. This shows that a parent lacks emotional maturity: Instead of using language to express their frustration, they resort to physical violence. A lot of adult children are still healing from the trauma of being physically abused as kids.

As an adult, a sign is that when you try to have a conversation with a parent about harm they may have caused, they deflect and defend themselves. They lack accountability. They have a very difficult time owning their actions and tend to blame. So they’ll say, “Well, you were a problematic child, so I had to treat you this way.” They might say, “Even now, as an adult, you’re irresponsible, so I have to scream at you. I have to talk down to you.”

Another sign is disguised hostility. A parent will say cruel things under the guise of friendliness, like “Well, I’m really surprised that you have a date tonight because, you know, you’re so big. You’ve gained so much weight. But I’m so happy someone wants to date you.”

But I think the number one thing is pathological lying. They gaslight you because they have a different version of the story. They have this inability to see beyond themselves. Everything is about them, and how they feel—not how their child feels.

How do you know if you should work on a relationship like this or just end it?

Attempts at repairing ruptures are important, and that is often the first step I encourage people to take. There are parents who are not aware that their behaviors can be abusive, because parenting is often intergenerational, and intergenerational trauma gets passed down through the family system. So parents engage in toxic behaviors because that’s how they were raised. You could say: “Your actions hurt me. You say you love me as a parent, and I want you to understand that I don’t feel loved when you speak to me this way. I don’t feel loved when you talk down to me.”

The first step is being vulnerable enough to say, “You’ve hurt me, and I need you to understand how you continue to hurt me.” Based on how they react, you’ll know whether or not it’s possible to repair the relationship.

How can you prepare for this painful conversation?

The first step is seeking support, which can look like going to a therapist, group therapy, or joining a support group. Make sure you’re surrounded by people who can validate your experience, people who are not going to judge you, people who can listen and hold space for all the things that have happened.

Next, you need a clear plan for what you are going to say to your parent or parents. You could use the same language as I suggested above, but add sentences like:

- “I don’t feel safe continuing in this relationship, and I’ve decided I would like some distance.”

- “I’ve tried repairing our issues, but it feels like the best way for me to heal is to cut ties and no longer stay in touch.”

- “I feel uncomfortable with our current dynamic and would like to take a break. During this time, I won’t be conversing with you and the family or attending gatherings until I feel ready to reconnect.”

- “I would like us to have some space and would appreciate it if you respect me and this decision to have some distance.”

Does it have to be all or nothing?

When you’re in that contemplation stage, you might dip your toe in the water and then step back, like, I thought I was ready—I’m actually not ready. That is okay. For some, cutting ties can look like I blocked them. I went cold turkey. And for others, it’s gradual: I’m going to slowly step away; first, I’m not going to answer the phone calls. Or This holiday season, I’m going to skip Thanksgiving dinner and see how that makes me feel. It can be a very slow process. Also, remember that in that state of grief afterward, if you ever find yourself saying, I want to try again, that’s okay, too.

What if siblings or other relatives get angry with you?

Your aunt is calling you. Your grandmother is calling you. Your brother. Now everyone else is jumping into the mix, saying, “How dare you? I can’t believe you’re not speaking to your mother anymore.” For some people, family is everything, so you have to explain to them: “For me to be a healthy adult and for my nervous system to be safe, I actually have to cut ties with my parents.”

Again, this is why it’s so important to have a stable community environment—a professional one and a personal one—because there are so many intricacies that take place when someone decides to remove themself from a family unit. You need to have those supportive systems available to you because it can be heavy, and that is okay.

You write in your book that some people of color can be hesitant to tend to their mental health via therapy. Do you have any specific advice for them?

Support groups for people of color can be extremely helpful and inexpensive compared to therapy. Many of these groups are led by therapists. To find therapist-led groups, visit directories like Psychologytoday.com. Nonprofits such as Mental Health America and NAMI also share resources where people can find support groups in their local communities.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Jane Burnett is an Assistant Editor at Oprah Daily, where she writes a variety of lifestyle content for the editorial team. She's a journalist with a pop culture sweet tooth—when she isn't catching up on celebrity news, she's usually listening to a podcast! Jane was previously an on-air reporter in local news, and worked at Thrive Global, Ladders News, and Reuters. She also interned at CNBC through the Emma Bowen Foundation, and is a member of the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ).